Opinion - Modern disdain

What are we chasing anyways?

The car, cash, credit card, condominium and country club originally started as a tongue-in-cheek mantra to represent “The Singaporean Dream” but now represents a pious desire along the Singaporean pipeline.

It seems that Singaporeans are growingly affected by some sort of pursuit - whatever “affected” means. For the schoolchildren, chasing top grades and yearning for prestigious opportunities, scholarships, accolades form most of the academic stress today. Take a quick look on SGExams Reddit page and it becomes clear that students are perpetually worried about something…

|

|---|

| Students, too, are affected by the “chase”, as it seems. |

I should preface this by saying that this is not a fault on said student’s part, but it is a result of the fear of losing out: when everyone’s chasing after something, not being part of the chase makes you a loser. And of course, this is part of a bigger phenomenon altogether, not just specific to schoolchildren: enter meritocracy.

I was recently reading “The Meritocracy Trap” by Daniel Markovits. Where meritocracy is the aspiration of a society to be apparently fair, just and equal, Markovits argues that meritocracy itself embodies neither of these values even if it initially set out to be. For what its worth, meritocracy is the root of radical inequality and actively stifles social mobility, and most upsettingly, makes people miserable, something which a growing number of the working Singaporeans now realise.

Much of this meritocratic belief is so ingrained in Singapore’s social fabric that it is almost intuitive and natural to think of one’s achievements as a result of his merits alone. And, society is doubling down on this: just 10 years ago, local admissions to academic institutions were purely based on academic performances alone: we had almost no concept of a holistic consideration for prospective students. Today, this could not be further: at each level, we have policies that encourage accolades and acknowledge students who achieve, forming a distinct mode of admission where academic performance is markedly less important. In reinforcing such a pursuit of merit, the message is now sent out: since we now holistically consider a student, what else is there for the student to be dissatisfied about, other than his own incompetence?

I raise this counterpoint: how else is competency measured in a race where people pay for advantages? How else are the less-wealthy supposed to fight an upwards better against the wealthier students who take part in enrichment classes since young and are part of a multitude of tuition classes that sharpen their academic abilities to a level that the less privileged will never envision? For a sizing, the most prestigious tuition centers offer a variety of classes starting from nursery(!) to junior college levels. For an example, I refer to The Learning Lab, a centre known for pushing students to enter MOE’s Gifted Education Programmes (GEP) and Integrated Programmes, both of which are aimed at the top percentiles of a student cohort. The “cheapest” classes start from $408 a month and the priciest are valued at almost S$600! Certainly, the Singapore tuition industry is a case of “willing-buyer, willing-seller”. Yet, for a nation who affords, or attempts to afford, their way into education programmes originally meant to measure a student’s proficiency, the proponents of meritocracy who still argue that the Singaporean education system is wholly merit-based could not have been more blinded from the truth. In 2021, the tuition industry was valued at S$1.4 billion, a marked high valuation, even amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. This just goes to show that the pursuit continues regardless of the impacts of a life-changing virus outbreak.

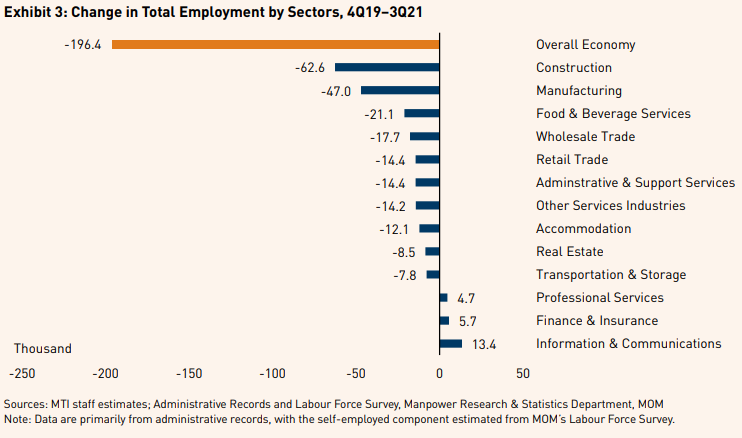

The students who fall behind come from families who have their employments affected by the employment market during the pandemic itself. Across the pandemic, it is apparent that those affected employees come from sectors associated with lower social-economic statuses, like the construction and the food and beverage industries. The industries that show growth are unsurprisingly white-collar in nature.

I personally detest the idea that people who excel in the rat race are the supposed winners and those who fall behind are labelled as such. Those that refuse to join the race are promptly cast aside as deadweights of our society: lumpenproletariats if you will.

Singaporeans are still perenially overworked, according to the Kisi Index, coming in as the second most overworked nation out of 50 in-demand cities. The situation would be mediated if said work corresponded to equal reward, but that is rather untrue. For such a make-believe system, it is no wonder that Singaporeans are growingly disdain.

As a youth that freshly walked out of 12 years of education just this year, I consider myself to still have that sparkle in my eyes. As much as I hope to live in an ideal society that provide for equality and equitable opportunities across the nation, I come to realise that that, in and of itself, is an uphill battle. Perhaps one day, Singapore will finally fulfill its promise of equality by fulfilling its “promise of mobility”, as Professor Teo You Yenn writes in her book “This is What Inequality Looks Like”.

I am hopeful that with the way trends are, the concept of losing will be at least diminished when it is my turn to join the race. Perhaps walking would be just as acceptable as running by then.