Math - Some Musings for October

USEMO 2022 spoilers!

The USEMO 2022 happened just last month - and it so happened that it’s my first time penning down some thoughts and commentaries about the problems (and also first occurrence of a math post on this blog!). As grading comes to an end, I thought it’d be a novel attempt for me to do so.

Specifically, I will first walk through my random thoughts and problem solving processes, and then discuss the rubrics and the performances for the respective problems. As a caveat, I am busy for the next month so this post merely gives pre-emptive discussion of the effects of the problem. The official statistics will come when grading officially concludes!

Since this is my first post of its kind, it’s best I introduce some “grading” terms. This year there were some elegant problems, and I’m excited to feature two of them: USEMO D1/1 and USEMO D1/2. So spoilers ahead!

-

0+/7- Problems are worth 7 points each. Personally, before any serious reading happens, I categorise a solution as either 0+ or 7-, corresponding to whether there is a reasonable promise of a full solve. For scripts in the 0+ pile, points are awarded for any specific non-trivial progress. For scripts in the 7- pile, points are deducted if there are non-trivial mistakes, according to the grading rubrics.

The general unspoken law is this chart, with common scores in bold:

Points Progress 7- Fully solved, possibly with small errors 7 Fully solved, or excusable slips, i.e. in calculations 6 Tiny slip that is easily repaired, i.e. incomplete casework 5 Small gap or non-central mistake, i.e. logical gaps 0+ Unsolved, or partial progress with crucial idea(s) missing 2/3 Serious progress that could be extended to a full solution 1 Non-trivial progress that is crucial to any promising solution path 0 No progress or immaterial work This is by no means a sympathetic grading principle: it rewards solutions that actively work towards a full-solve as opposed to solutions that grapple around in the dark. I think of this as a qualitatively quantitative rubric: as opposed to school math, points are not awarded for messy or bulky work!

On the other hand, we’re not opposed to awarding partial credit for some promising progress, but these are given under stricter scrutiny

-

Additive/Non-additive points We differentiate marking points based on whether they are additive or not. For an example of additive points, D1/1 allows 1 point for a correct answer and 1 point for a correct construction. In this case, we say these 2 points are additive, so the usual $1+1=2$ points are awarded.

On the other hand, non-additive points do not accumulate. As an example, in D1/2, 1 point is awarded for proving that $\sum f(a_i)$ has the same sign throughout, and 2 points for proving $f(x) > 0$ is true for either $x < 0$ or $x > 0$. If a solution proves both, then they are awarded 2 points only. That is, we have the “nomenclature” $1+2=2$ to indicate that if a submission scores either of these 2 points, the higher is awarded instead of summing the 2.

In general, olympiad grading is pretty wacky. It’s not every day that you see things like $1+1=1$ or $1+1=7$ in an official math document.

D1/1 Sticks covering a chessboard

A stick is defined as a $1 \times k$ or $k \times 1$ rectangle for any integer $k \geq 1$. We wish to partition the cells of a $2022 × 2022$ chessboard into m non-overlapping sticks, such that any two of these $m$ sticks share at most one unit of perimeter. Determine the smallest $m$ for which this is possible.

Holden Mui

Thoughts and Writeup

As is the unwritten USEMO tradition, P1 is somehow always (with a sample size of 4) harder than P2, and thus the learning point: attempt all 3 problems!

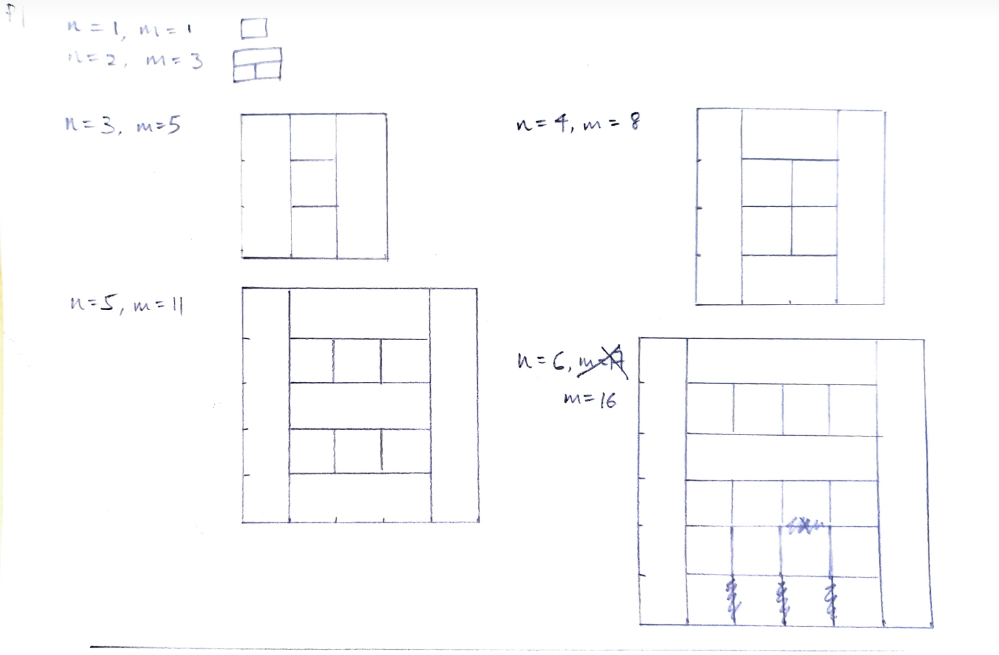

Anyways, we start this problem with a sketch.

|

|---|

| Grr…. it’s not symmetrical |

With some hindsight, this is one of those problems where the equality case and the bound are both slippery to arrive at. It took about 20 minutes of trial and error just to convince myself that these were the equality cases, and as it is clear, the equality case depends on the choice of $N=2022$ (I conjecture that this is due to parity, which explains the anti-symmetry). In fact, if we naively continue the pattern for even $N$ by using a central column, we get a bound of $m \sim C(N^2-N)$. Fortunately, some sketches convinced me otherwise.

Okay, so I’m convinced that my constructions are maximal, and fortunately they are easily generalisable. They give a bound of $m \sim C(N^2-2N)$, and now I turn to proving this bound: which is the bulk of the challenge.

Seeing that my constructions were easily generalisable, I start by trying to recursively extend my diagram from $N \times N$ to $(N+2) \times (N+2)$. Looking back at my diagram, I realise that the main bulk of the action is concentrated in the central $(N-2) \times (N-2)$ squares, with the long sticks at the sides of the chessboard. Thus the first (hopeful) claim:

Given a valid tiling of the chessboard, we can “re-stick” so that the sides are always filled by long sticks, and this re-sticking does not increase the total number of sticks used.

At this point I stumbled for a long time trying to work with the $4 \times 4$ case, but it turns out to be really difficult and slippery - at least I couldn’t figure out how to complete the argument, and none of the submissions I graded proceeded in this way (maybe it is impossible…). The difficulty of re-sticking lies in that each row is dependent on the previous row’s arrangement, so it might even be the case that for a $N \times N$ chessboard, you have to peek backwards $N-1$ times, as I did for $N=4$. I stubbornly stuck to this idea for the next 1.5 hours, but not much luck.

In hindsight, I wasn’t sure what I was trying to go with this claim either - I don’t have any clue on how to continue with this idea even if I could prove the claim.

Now finally I try the second-most obvious re-interpretation of this set-up: view this chessboard as a board of $(N+1) \times (N+1)$ lattice points, and connect each pair of adjacent lattice points with an edge: then each stick covers some (possibly zero) of these edges. Call a covered edge a shy guy (yes I referred to them in this way) and let $S$ be the number of shy guys. Then, we seek

\(\min{m} = N^2-\max{L}\).

First, the condition that any two sticks share at most one unit of perimeter is equivalent to each lattice point being the endpoint of at most one shy guy.

Next, each corner of the chessboard is adjacent to no shy guys, and each of these corners has an adjacent lattice point that is itself adjacent to no shy guys.

Hence, for a general $N$, $L \leq \left\lfloor\frac{N^2-4-4}{2} \right\rfloor$ so

\[\min{m} \leq \left\lceil{\frac{N^2-2N+7}{2}}\right\rceil.\]For the competition experts, this is a “global” perspective of the problem, as opposed to the “local” consideration of the interactions between each individual stick. We instead look at the overall effect of all the sticks at once, and in hindsight, this is the more logical approach because of the “look-back” effect: it is not clear how each preceding layer of sticks determine the next, and throughout grading, I don’t think that a local approach arose at all.

Rubric and Performance

For how tricky this starting problem was, I suppose the rubric was very forgiving. In particular, additively,

- 1 point for the correct value of $m$ even without justification; and

- 1 point for a correct construction.

If $m$ is weaker, the rubric also allows, non-additively,

- 1 point for the construction which naively tries to extend the case for odd $n$ to even $n$;

- 1 point for proving $m \geq cn^2$ is necessary for any $c\geq\frac{1}{3}$; and

- 2 points for proving $m \geq \frac{1}{2}n^2-cn$ is necessary for any $c\geq 1$.

As of now, there seems to be about $30\%$ of 7- solutions, which at a glance seems to be pretty high, but my guess is that people are much more unwillingly to let go of problem 1’s. After all, a starting problem as inviting as this one doesn’t seem as hard as it actually is!

My personal grade for this problem: $5/7$. It has a very simple statement and this already makes it very inviting. It’s a slight shame that this is slightly misplaced IMO and I think it would be more appropriate if it was swapped with problem 2.

D1/2 Geassy and Classy Analysis

A function $\psi \colon$ ${\mathbb Z} \to {\mathbb Z}$ is said to be zero-requiem if for any positive integer $n$ and any integers $a_1$, $\ldots$, $a_n$ (not necessarily distinct), the sums $a_1 + a_2 + \dots + a_n$ and $\psi(a_1) + \psi(a_2) + \dots + \psi(a_n)$ are not both zero.

Let $f$ and $g$ be two zero-requiem functions for which $f \circ g$ and $g \circ f$ are both the identity function (that is, $f$ and $g$ are mutually inverse bijections). Given that $f+g$ is not a zero-requiem function, prove that $f \circ f$ and $g \circ g$ are both zero-requiem.

Sutanay Bhattacharya

Thoughts and Writeup

I personally think this is a very neat problem to demonstrate proof techniques, and a beginning student might find this problem instructive in the same sense: the set-up for the problem hints at you for the first step!

Throughout this write-up, I refer to $\sum a_i$ as the first sum and $\sum \psi(a_i)$ as the second sum, just for laziness.

We are told that a function is zero-requiem if the 2 sums are not both zero. The natural instinct would be to investigate what happens if exactly one is zero. Of course, we start with the first sum.

Since this is the only structure of a zero-requiem function, it makes sense that the first sum heavily restricts the second sum. My first claim hinges on this intuition explicitly:

Claim 1: For $\sum a_i=0,$ $\sum \psi(a_i)$ is either always positive or always negative (otherwise, what else could you conclude?).

The proof of this claim is of course by contradiction. I raise three different interpretations.

1. System of equations (mine) Suppose there exists two sequences $\sum a_i=\sum b_i=0$ such that $\sum\psi(a_i)>0$ and $\sum\psi(b_i)<0$.

Then,

\[-\left(\sum a_i\right)\left(\sum\psi(b_i)\right)+\left(\sum b_i\right)\left(\sum\psi(a_i)\right)=0\]and

\[-\left(\sum \psi(b_i)\right)\left(\sum\psi(a_i)\right)+\left(\sum \psi(a_i)\right)\left(\sum\psi(b_i)\right)=0.\]Then, by subtracting both equations, we get a contradiction.

My personal opinion is that this is a pretty natural idea to go by, by interpreting the “second sums” as a system of equations to satisfy.

With this, there are other interpretations of course: here is a slight modification of the official solution’s lemma.

2. Vector Walk (official) We interpret the vectors $p_i=\left(a_i, \psi(a_i)\right) \in \mathcal{P}$ as a sequence that forms a walk in the cartesian plane. Our claim is equivalent to there being a line that splits the plane into half, such that every walk lies in exactly one of these half-planes. We shall refer to the “first” and “second” sums in the same way as above.

Again, we assume that the first sum is zero but the second sum is not. Then, suppose for the sake of contradiction that the walk eventually reaches the origin, so

\[\mathcal{O}=\sum_{p_i\in\mathcal{P}}k_ip_i,\]where $k_i$ are positive and rational and $\sum k_i=1$. However, we are able to choose a large $K$ for which $k_iK$ is an integer for all $i$. Now multiply throughout the equation by $K$, so we have a walk that returns to the origin. But this means $\sum a_i=\sum \psi(a_i)=0$, a contradiction.

3. Vectors that form a triangle (contestant) In another interpretation, this claim also says that for large $n$, we can find 3 vectors in a triangle that are sufficiently far apart so that their weighted average is the origin (by scaling and translating).

Now, we are ready to finish off the problem.

Again, assume $\sum a_i=0$. Since $f+g$ is not zero-requiem, then $\sum f(a_i)$ and $\sum g(a_i)$ have opposite signs, implying $f$ and $g$ have opposite signs by our lemma. However, because $f$ and $g$ are mutual inverses,

\[\sum f(a_i)=\sum (fg)(f(a_i))=\sum (gf)(f(a_i))=\sum g\circ ff(a_i).\]This happens if $\sum a_i=0$ and $\sum ff(a_i)=0$, as required.

Rubric and Performance

My personal feel is that this problem is an instructive one: each step comes naturally (or that I was just lucky that I chanced upon the right idea instantly). I rate this easier than D1/1, but the scores on this problem don’t seem to reflect this sentiment: I expect only about 6 solves out of 30.

This seems to be a repeat of IMO 2017, where P2 obstructed any would-be non-trivial progress for P3. All things considered, I think this problem has a cool setup with the Code Geass reference, and it is easily understandable even by non-competitive students once we strip down the references. I give this a 5/7 as well, for the same reason as D1/1 that it is misplaced in my opinion.

The rubric is fairly liberal with partial credits in the sense that points are scored for following the natural set-up of the problem. Here, the non-trivial progress is our claim, and interestingly, the rubric awards different marks for the 3 interpretations (actually there are 2, since 2 and 3 are quite equivalent). These are of course non-additive.

For our first interpretation,

- 3 points for the claim.

- 1 point for showing $\sum a_i=0$ implies $\sum \psi(a_i)$ is either always positive or always negative.

- 2 points for showing (without loss of generality) $\psi(x)>0$ for all $x>0$ (or $x<0$).

For the second and third,

- 1 point for conjecturing that the walks lie on exactly one half-plane, i.e. there exists $C$ such that $f(x)>Cx$ or $f(x)<Cx$ for all integers $n$ (I like to say that $f$ is superlinear).

- 4 points(!) for proving this conjecture.

The key difference between these two interpretations is that the latter one finishes almost instantly. Suppose $f$ and $g$ are superlinear, with constants $C$ and $D$. Then the finishing move boils down to considering the cases when $C>0$, $D>0$ and $C, D<0$.

Final words

As a repeated reminder that the Covid-19 years have been a blur, this is my third year grading for USEMO and it is still a joy to see so many volunteers from around the world rallying together for a competition like USEMO. And really, the math community would be nothing without its people. Personally, I’m grateful that there’s a place for both established and aspiring competitors, as well as slow folks like me who enjoy the luxury of being involved in competition math while sipping on tea.

Either way, this is yet another successful run of the USEMO, so kudos to Evan and the team for making it happen; and a special mention to my fellow graders for working out the gallons of smoke on the submissions for D1/2!